The first direction focused on a crane—a revered symbol in Chinese mythology that represents longevity and wisdom. While contemporary in line weight, we had some wiggle room as to whether it looked old or new through color.

The second direction was a literal combination of Chinese and American craft beer aesthetics. The four Chinese characters nested perfectly within big, friendly English typography. Color and and pattering would round out the system.

We were proud of where we arrived and the Prodigy team loved both directions. But then we hit a snag.

Big trouble in little CODO. (Sorry, I’m so sorry.)

After sharing our initial branding concepts with the Stateside Prodigy team, they shared the work with their community in China (comprised of home brewers, beer geeks, bar owners, and distributors). This round of critique brought up a frustrating and humbling issue; what we had made looked Japanese. Not overly Japanese, but enough that it would immediately stand out to a Chinese beer drinker. Turns out, a lot is lost in translation when you’re unable to experience something as foreign as China firsthand.

In response to this, the Prodigy team floated what would become the most important element of this entire project—“CODO, will you come to China with us so you can experience what we’ve spent the last month and a half talking about?”

After sorting out Visa applications and a whirlwind itinerary, our bags were packed and we were ready to go. One 24 hour layover in California (which allowed us to visit our friends at Seven Cities Bev Co.) and a thirteen hour flight later, and we landed in Beijing. Jetlagged and weary, we immediately met with the Prodigy team, including a gentleman named “Tiger.” Tiger is thirty years old, boasts 27 stab wounds (scars, technically), carries two phones—“one for business and one for pleasure,” and loves Katy Perry. We knew right away that we were in good hands.

Our team assembled, we set out for drinks, food, and more drinks. We hit up a few prominent craft breweries in downtown Beijing—Jing A, Slow Boat, and Great Leap, and soaked up as much of the local night life as we could. It was interesting calling out the same trends and tropes we see in American craft beer. Besides the too-familiar exposed brick, hanging Edison bulbs and subway tile, you’ve got your dyed in the wool “Hipster Brewery,” your “Dad Brewery,” and the venerable “OG Craft Brewery” that makes amazing beer but is now looked upon as the Establishment (despite the fact that they pioneered local craft beer). Perhaps one of America’s biggest exports is cynicism?

Jing A Brewing (left), Slow Boat Brewery (center), and Great Leap Brewing (right)

The next day, or night—at this point, it’s all a blur—we took a 2-hour bullet train to the contract brewery in Handan. Their facility was fascinating, if not surreal—it’s a German brewery in China. We had traveled from America to China and then suddenly found ourselves in German brewery. Chinese regulations prevent you from operating your own brewery unless you’re capable of producing 12,000 or more bottles per hour. This causes many of the craft brands to rely on this particular contract brewer. After touring their entire operation, we ended the visit with lunch and some fantastic beer in their brewpub.

Handan train station (left), visiting the contract brewery (right).

Afterwards we made our way back to the train station and headed back to Beijing. But our night wasn’t over yet. After a meal of hot soup where we ate pig brains, pig blood, and cow stomach (a first for me), we decided to visit Great Leap’s Hutong brewery. The Hutong are nearly thousand year old neighborhoods comprised of alleyways and courtyard homes. Hole-in-the-wall doesn’t do this bar justice; it’s more like a hole in a wall in a maze. However, once inside, we felt like we were back in the States. This place could easily pass for a Brooklyn dive bar.

Cow stomach and pig brain (top left), Hutong location of Great Leap Brewing (bottom left, right).

This night started out productive. But after a beer, and then another, and another, and another, and another… for those who are questioning the necessity of trips and nights like these—whether we’re winding our way through Sioux Falls, South Dakota, or spending a week in Beijing, you often get the most color on a project and a community and the opportunities therein by immersing yourself with the locals. This entire day and night were spent discussing politics, pop culture, and the interesting intersection of American and Chinese craft beer.

The following morning was a bit hairy, but we persevered and all agreed to do something touristy. I generally avoid stuff like this, but after seeing the Great Wall in person, I may set those reservations aside more often. This beautiful, rural setting created an abrupt, and welcome, contrast from the fast moving and overwhelming urban scenes we’d spent the last few days experiencing.

Mutianyu section of the Great Wall looking west (left) and looking east (right).

We spent our last evening at the British-owned, hipster-friendly Arrow Factory Brewing. This place definitely had a cool-yet-fun vibe with a distressed interior and large posters of their labels (solid branding and great beer). It was a nice end to our Beijing craft beer tour, and the next morning found us headed home on another thirteen hour flight.

Arrow Factory Brewing (left, center), Beijing airport customs (right).

Back to reality

Now we’re back in lovely Indiana (no cow lung or pig brain entrées in sight). After a few days to decompress, we’re able to sit down and formalize what this should all look and feel like, and where we had gone wrong the first time around. Working with the Prodigy team, we began to define anew their audience, brand essence and what positioning and messaging we needed to explore. The answer; American Craft Beer. You read that correctly—we had to travel nearly 7,000 miles around the world to realize that the Chinese craft beer consumer wants a Western-made beer brand. Or at least, a craft beer that has some semblance of America. We had to leave home and see one of the most beautiful places we’ve ever experienced to see that it had to look somewhat familiar to what we’ve seen over the last 8+ years of working in this industry.

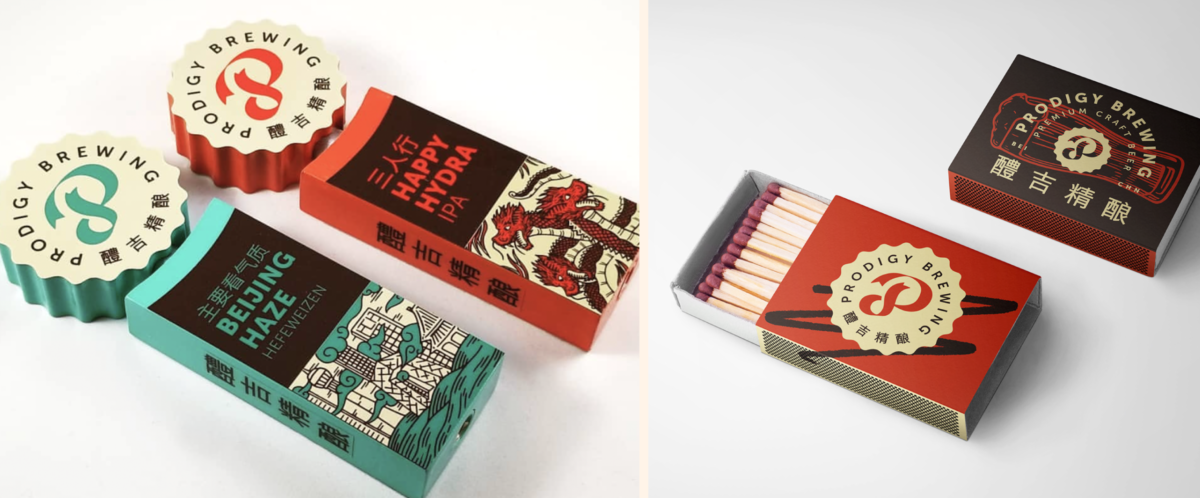

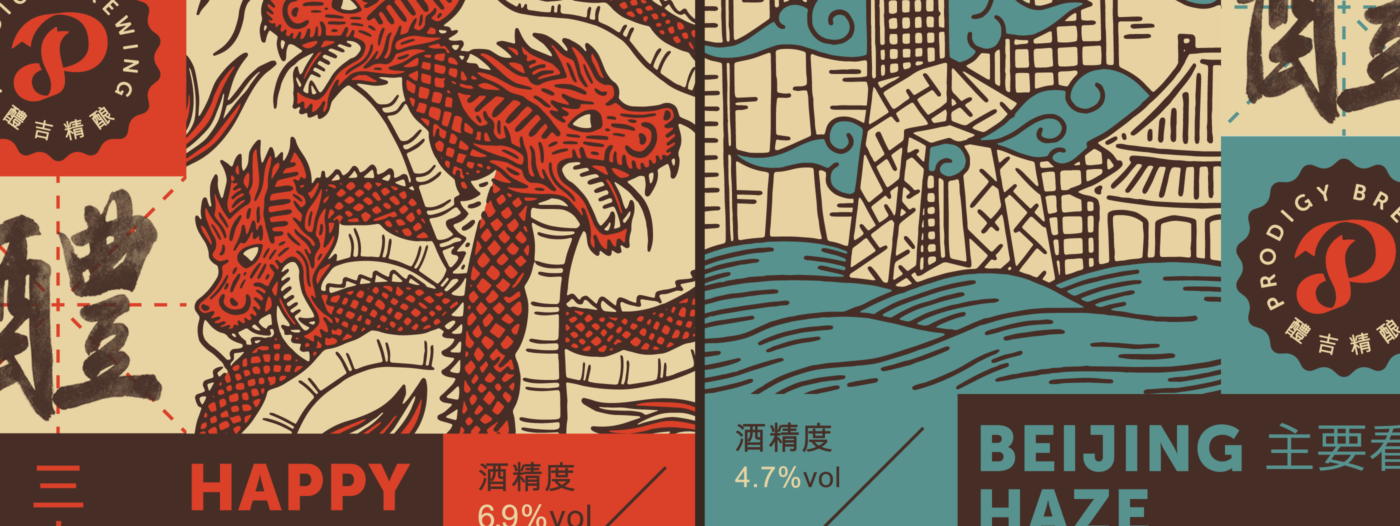

This insight in hand, we built out a brand identity that looked vaguely American, while retaining key pieces that would resonate with folks in China. The main icon was inspired by ribbons (a reference to academia; red ribbons are often used in China as a good luck charm), and a combination of the letter ‘P’ and the lucky numeral ‘8.’ The icon is set atop a bottle cap seal (combining academic and beer references). The color palette has a warm, nostalgic feel that has been a staple American craft beer aesthetic for years. Finally, we rounded out the identity with rule lines, grid lines and hand-drawn elements to further reference academia and expertise. This spoke to the original brand essence and positioning of Prodigy as the intelligent craft beer choice or an enlightened, American craft beer academic who’s fallen in love with China and its culture.