Section 4. Recession & Inflation

We listed several article headlines earlier that outlined how hard seltzer is dead and how Gen Z drinking rates have fallen off a cliff. A similar (overly-simplified?) theme has emerged around the recession and craft beer. If everything costs more, then surely consumers are trading down (buying cheaper offerings).

Remember, beer is “recession proof.” Or, is it recession-resistant?

Either way, we’ve been tracking this idea for the last year and can’t find any conclusive data that shows this is actually happening in craft beer. And besides, the idea of a category-loyal buyer who, in times of plenty, may spend a few hundred dollars a month on craft beer suddenly tightening her belt and buying a 30 rack of Busch Light seems… improbable.

I do think there’s a case to be made for consumers, even category-loyal ones, simply buying less though. Discretionary spending is down because we’re in a terrible economy—we have been since early 2022. So what does this all mean for your customers?

Let’s explore a few recurring conversations we’ve had in our project work this year.

On the perils of going budget?

Can your brewery (safely) enter the budget market?

*This section was previously published on our Beer Branding Trends Newsletter. Subscribe here if you’d like to receive timely insights like this throughout the year.

—

We’ve had interesting conversations with several Bev Alc groups (breweries and distilleries) over the last year about opportunities for creating budget products specifically as a hedge against the economic downturn.

To give a concrete example: We’ve spoken with a few breweries who are considering a large pack light lager approach. Specifically, they want to create a real deal, cheap light lager that would be priced along the lines of a Bud or Miller 12-pack—so somewhere between $10.99 and $12.99 per.

At first blush I have two competing thoughts:

1. This entire notion seems like more of a Big Beer / Large Craft conversation because in order to enter a lower cost space, you have to have the volume, both in ingredient costing, production capabilities and sales, to compete with a variety of already entrenched brands.

2. But then creating a budget option also makes sense at first glance. If our customers are getting hammered by inflation (and at the gas pump, and on increasing rent, and groceries …) then let’s give them a cheaper option that they can still enjoy. And for what it’s worth, all of these conversations were in this spirit—these people care about their customers and want to keep serving them.

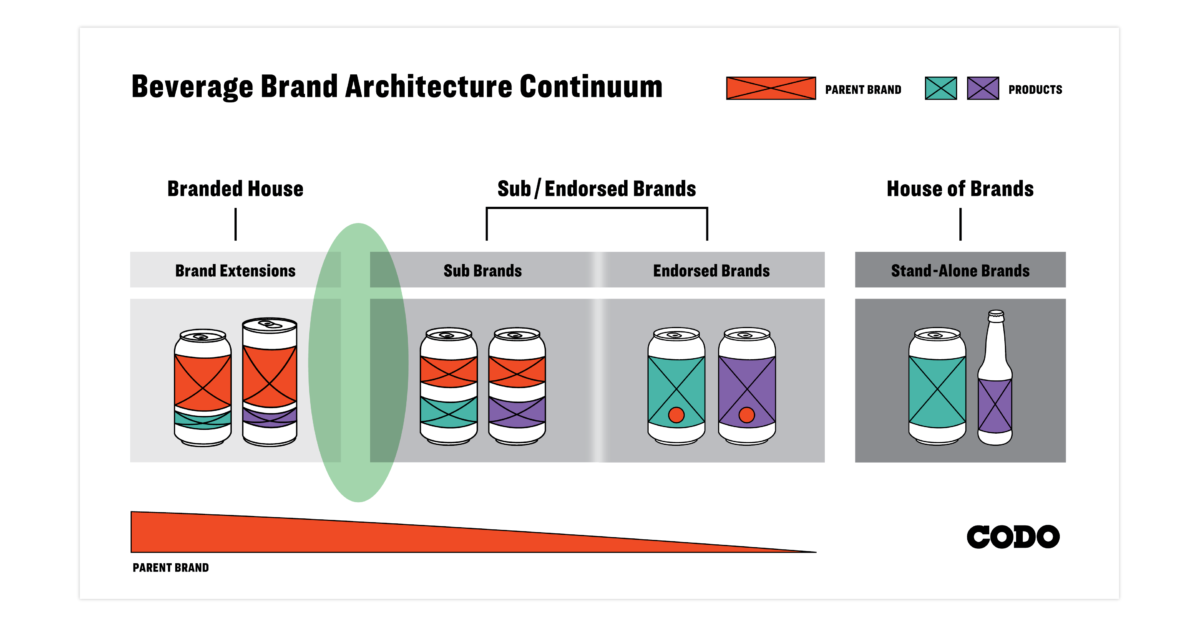

So while noble, I want to address this idea head-on because of all the Brand Architecture strategies we’ve discussed over the years, releasing a markedly cheaper product can potentially be one of the most damaging moves you can make.

With the economy seemingly mired in place, I imagine that these sorts of plays could become more common over the coming year. In that spirit, let’s explore why creating a budget offering can be so dangerous and discuss some practical ways to minimize the risk should you decide to ignore everything I’m saying here and move forward anyway.

Why is this risky?

Can something be high quality (craft) and cheap at the same time? Not a great deal, per se, but a premium quality product at a mass market price?

Can you find a luxury vehicle for $15k? Or how about a luxury watch for $200? Can you have an artisan burger at a McDonald’s price?

You can’t. It’s just not possible.

You can’t use high quality ingredients, and proper manufacturing methods, and pay your people well and still offer a high quality thing at a cheap price. There’s always a catch.

And we all knows that.

This isn’t how the world works and anyone who is paying attention would view this with suspicion. What corners did they cut to get their price this low?

When you buy a 12-pack of Bud Light, you’re buying it because it’s cheap. No value judgment there—the beer fills that mass market role well.

By attaching your brand name directly to something that is of lesser quality than your typical offering, you are creating a potential level of mistrust that can spread to the rest of your portfolio.

“Yeah, they shit out this light lager. But I’m sure their IPA is up to snuff.”

How to determine whether or not this is a good move

Let’s start by working through three key questions:

1. Is there a market opportunity?

The first (and most obvious) point to consider when launching any new product is whether or not there is an actual need. Do people want something that they’re not currently able to find? Does your market need XYZ (a light lager, a budget seltzer, a cheap NA beer, affordable well spirits, etc.)?

I can’t think of a market where this sort of unmet demand exists. For any of this. That doesn’t mean there’s not a market out there where this strategy could work, but there’s a beer at basically every price point in every market in this country already. And a glut of entrenched options in the budget space (i.e. Domestic Sub Premium @ ~$18 per case to Domestic Premium @ ~$23 per case tiers).

2. Can you compete?

The second point is whether or not you can realistically compete.

I’ll use the light lager example from above because it’s the most immediate move in the craft beer context. Can you, a small (hell, even medium size) craft brewery, get your COGs to pencil out in such a way that you can actually compete with Big Beer on price (and still stay in business)?

And another fun wrinkle: Will your distributors, who are likely also delivering truckloads of that same Big Beer, be open to carrying this new product?

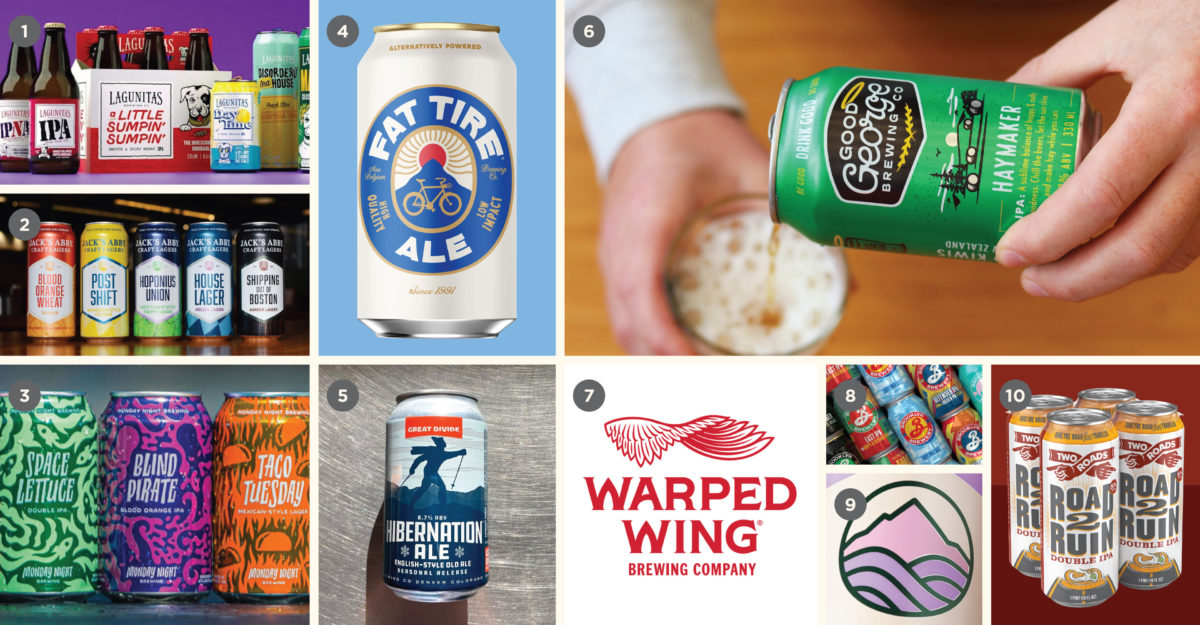

And let’s step down from Big Beer. Can you even compete with Big Craft? Can you price your beer such that you can compete with the Yuengling’s and 805’s and Oskar’s Lager’s of the world (and still stay profitable)?

We’ve worked with more than 75 craft breweries, including some of the largest in the United States, and I don’t know if there’s a single one we’ve come across that could actually pull this off at scale.

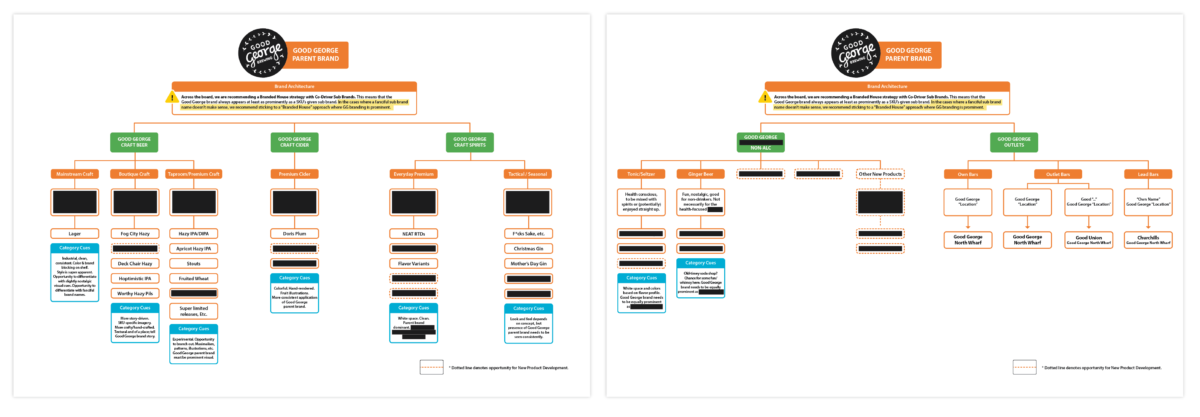

3. How will this affect your Parent Brand’s positioning and reputation (and ability to charge a premium)?

Our third point, and perhaps most germane to this issue itself, is how your Parent Brand will be affected by this move. Not just in the short term, but over the long haul.

Can you safely maintain a premium (craft) positioning at the parent level while also offering a lower cost, budget option?

The real risk in all of this is of repositioning your Parent Brand itself. If you release a cheap (super cheap, budget) beer, what will that say about the rest of your portfolio?

You can undo years of hard work in one move by changing what your Parent Brand stands for in your customers’ minds.

And that change won’t be positive.

Craft on Craft M&A

Finding strength in numbers

Craft M&A activity has been happening for years. Big craft outfits selling to multinationals. Cross-category sales (brewery sells to cannabis companies, Big Soda (or Big Energy) invests in and/or partners with a brewery, etc.).

And indeed, Modern Times selling to Maui, or Stone selling to Sapporo and Bells selling to Lion are all major stories.

But this trend specifically highlights the rise in smaller (when compared to a Stone or Bells) breweries joining forces. These deals usually combine specialties of both parties to complement each other. E.g. we’ve got brewing and product innovation and distribution dialed in, and you’re good at the hospitality side of the house. Let’s partner to make a stronger outfit.

A few examples here include: Urban South x Perfect Plain Brewing. Roadhouse Brewery x Melvin Brewing. Saucy Brew Works x Cartridge Brewing. Bishop Cider x Wild Acre Brewing. Mass Bay Brewing (Harpoon) x Long Trail Brewing. Finnegan’s Brew Co x Hairless Dog Brewing. Faubourg Brewing x Made By The Water. Eagle Park Brewing x Milwaukee Brewing. Drake’s x Bear Republic.

A note from the editor here: This trend could have just as easily been in the Brand Architecture section above because there are some major brand and messaging issues to work through if you’re buying (or merging) with another brewery. But I believe the increase in these deals that we’re seeing is a direct result of the competitive market and economic environment we’re in today coupled with the challenges of running and growing a brewery coming out of the pandemic.

We’ve seen branding inquiries and projects centered around brewery acquisitions almost every single month for the last year. These range from rebranding a brewery post-acquisition, to Brand Architecture projects to sort out how the two companies can blend, to conducting a Brand Audit on behalf of a national hospitality group to determine what value they should place on the Brand of a brewery they were planning to purchase.

We’ve seen so many of these inquiries, particularly the rebrand or brand refresh post-acquisition variety, that we dedicated an entire issue of the Beer Branding Trends Newsletter to it last year.

Here’s an excerpt from that piece.

So you bought a brewery. To rebrand or not to rebrand?

Since about Q3 of 2021 to today, we’ve fielded loads of inquiries and projects centered around brewery sales. In most cases, these aren’t headline grabbing M&As like Stone or Modern Times, but rather, small-to-medium (say, 500–15k bbl per year) outfits.

So the people we’re talking to (and working with) are usually in one of two camps: They are either about to buy a brewery and want to figure out their immediate next steps from a branding and positioning standpoint once the deal closes.

Or they have recently acquired a brewery and as part of getting everything up and running during the transition, realized they need to address their branding and packaging in some way—generally a refresh or outright rebrand.

—

I’m not sure if all of this is a good sign or a bad sign. The industry has been around, in its current form, since 2010, so it may just be that there are a lot of founders who have been at this for 5–10 years who are ready to move on.

And let’s not forget 2020, in particular.

The industry is still dealing with fallout from the pandemic—mandatory shutdowns, revenue dropping as much as 90% overnight, major channel shifts, changed consumer drinking habits, obscene input cost increases, labor shortages, inflation, and recession… But unlike 2020, there are no stimulus checks or Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) funds coming. And the Restaurant Revitalization Fund (RRF) seems like it’s tapped out as well. And again, we’re in a recession.

So any one of these could be the deciding factor to pack it in for many founders.

I’m guessing here since CODO’s interaction in these scenarios is almost always with the purchasing party and not the outgoing group. (But this isn’t too hard to imagine, right?)

Either way, the reasons driving these sales don’t matter for our conversation today. What matters is that there are a lot of brewery sales happening right now in the United States. And I suspect this will continue over the next several years.

So back to those folks who are reaching out to us to discuss these sorts of projects. What do you do with a brewery’s brand after you buy it?

Let’s discuss this situation and give you some things to think about if you’re shopping for a brewery.

There are three important questions to consider whenever we discuss a situation like this with a potential client:

1. What are you actually buying?

2. Is there any visual and/or brand equity to be retained?

3. What is your vision for this brewery?

Broad Stroke Guidance

It’s tempting for me to tell you that you’ll need to revamp your branding after buying a brewery no matter how you answer these questions because this would set you up for a running start either way. But a strategically sound answer is going to be much more nuanced.

Here are a few broad stroke ideas for you to think about if you’re in this position:

When buying an established, popular brewery

The more well-known and established a brand (how long it’s been open, number of active accounts, annual bbl production, distribution footprint, etc.) the more likely you will want to retain (or at least honor in some way) the brewery’s visual and brand equity.

And it’s a safe bet that this equity is probably a driving reason for the purchase in the first place.

So in this case, you could go through some sort of refresh—address some pain points, clean things up and set your team up to manage everything better—but probably not a sweeping rebrand.

When buying a smaller (or even mid-size) brewery

If you’re buying a smaller, or newer brewery (limited production capacity, limited-to-no distribution, likely a small taproom, etc.), then you likely have more leeway to change things up in a major way.

So you might consider a thorough rebrand if that aligns with your vision and goals for the business.

As always, your project context, competitive set, broader brand strategy and goals should drive all of these decisions.