Direct-to-Consumer (welcome to the “Fourth Tier”)

Convenience as the ultimate value proposition

Direct-to-Consumer (DTC) is one of the most exciting things to come out of the COVID-19 pandemic. And smart money says it will be one of the largest forces to shape the industry over the next decade.

The laws surrounding shipping alcohol are messy and onerous, so DTC manifests in a few different ways. The most common approach we saw throughout COVID-19 has been online ordering in conjunction with curbside pickup. But the more exciting opportunity entails breweries shipping beer directly to customers (on a per-order basis or subscription plan). And there were a lot of legislative changes across the country last year to allow for more of this.

DTC and alcohol eCommerce sales were already trending up over the last few years, and like so many things in this report, the pandemic acted as a powerful tailwind (Drizly reports seeing a 1,000% increase in year-over-year (YOY) sales during peak pandemic lockdowns last year).

It’s easy to grasp why DTC is valuable during state-mandated lockdowns. But why will this persist long after we’re all back to some sort of normal? Convenience.

Convenience will be one of the most important drivers of our economy over the next ten years (this is a natural outgrowth of the Amazon “Prime-ification” of the world). Why go to the grocery store if I can buy something with one click on my phone? And to think that the alcohol shopping experience will be an exception to this trend is myopic.

The wine industry has been doing this for years (with $3 billion worth of wine shipped in 2019 alone!). And there’s a tremendous opportunity for breweries here. Everyone in America is ready for it—we all understand that by cutting out the middleman (with apologies to the middle tier), you can get razors, eye glasses, mattresses, beer and now even cars shipped directly to your door.

Third party groups like Drizly have been championing this for years, but expect to see larger alcohol beverage conglomerates move into this space with their own offerings soon. So whether you like it or not, your brewery should move on this if you haven’t already.

What are some other things that will come from this?

Look for social media to continue shaping eCommerce opportunities

Instagram became a powerhouse shopping experience with in-post ads linking directly to purchase opportunities throughout 2020. Look for TikTok, Facebook and even LinkedIn to ramp this up as well.

Will a DTC-first (and only) brand fly?

Will a direct-to-consumer only beer brand ever work? That’s not too far a leap from what well developed contract-brewed brands have been doing for years. Develop a compelling lifestyle brand, pour gobs of money into advertising, get the right technology in place to sell your beer and you’re off to the races. Maybe.

Provenance, authenticity and locality are all perennial value propositions in craft beer, so I have my doubts that a craft brand can credibly operate in this space entirely, but that doesn’t mean that DTC can’t be a major part of a brewery’s distribution and sales plan moving forward.

On the flip side, I think this model could work well for a non-alcoholic brand (since shipping regulations aren’t an issue) and Big Beer, with its Big Beer distribution network and Big Beer infrastructure. If someone is already buying a 12-pack of Coors each weekend, why not just have it set up for auto-delivery (via subscription) to your front door?

Shopping on a Mission

For those willing to leave their homes

Quick note: this trend is actually referred to as “Mission-driven” shopping in other press, but we’re rewording it to be clearer since “Mission-driven shopping” sounds like a cool cause-based thing. “If I buy this beer, the brewery will donate a 6-pack of N.A. beer to a thirsty family in need.” But it’s actually a much more mundane concept.

Shopping on a Mission is the idea that people are making fewer visits to grocery stores (or any other physical retail spot), but spending more money per visit to grab everything they could possibly need to hold them over until the next trip.

So what does this mean for craft beer?

For starters, if you’re in large-chain retail, you’re in a better spot to capture these sales. According to Nielsen, large breweries were posting 18%+ YOY growth throughout Spring 2020. This was driven in large part due to an increase in demand for multipacks (particularly 12-packs). We’ll discuss this in more detail here in a bit.

Building on that, this shift in shopping might have lead to a slight decrease in exploration (e.g. buying a new, untried 6-pack) and an increase in brand loyalty (e.g. Voodoo Ranger is always great. I’ll buy a 12-pack to last through the week.). But this is hard to quantify. Bart Watson, Chief Economist for the Brewers Association, reported that while grocery channel beer sales obviously increased during COVID-19, the growth that smaller craft breweries and larger craft breweries (and their flagships) saw from this period actually didn’t look that much different from what the sales data showed before the pandemic.

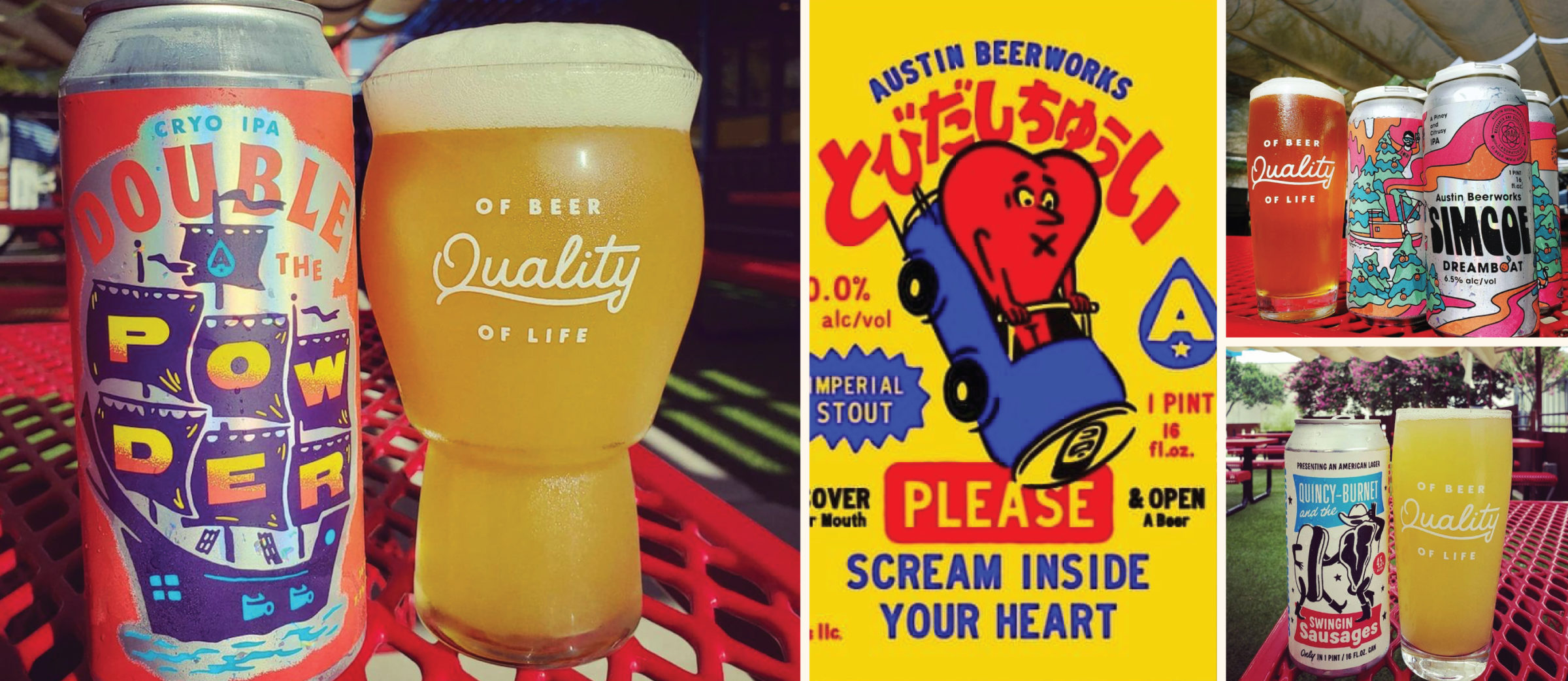

We’ve spent a good deal of time over the last five years discussing how flagship sales were floundering, but then they weren’t, but then they were again. And COVID-19 has rekindled this conversation. Whether or not flagships are actually selling more is up for debate, but anecdotally, when things went sideways in 2020, we saw dozens of breweries make moves to strengthen their core brands to build a repeatable base.

Aluminum Shortage

Feeling the crunch

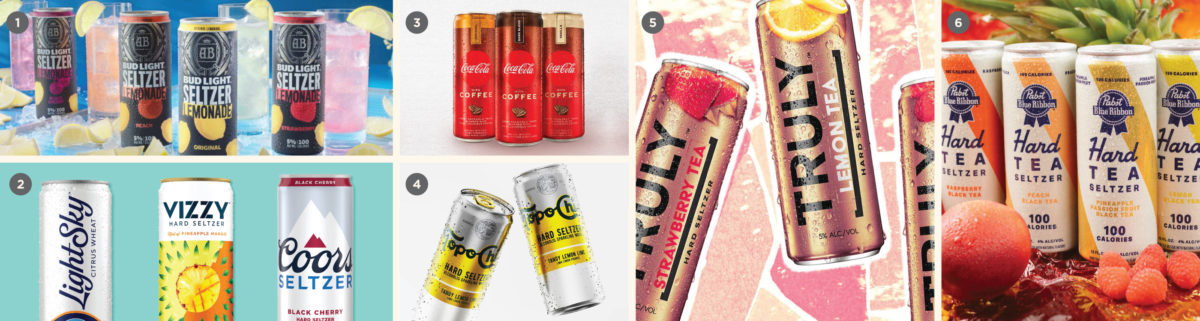

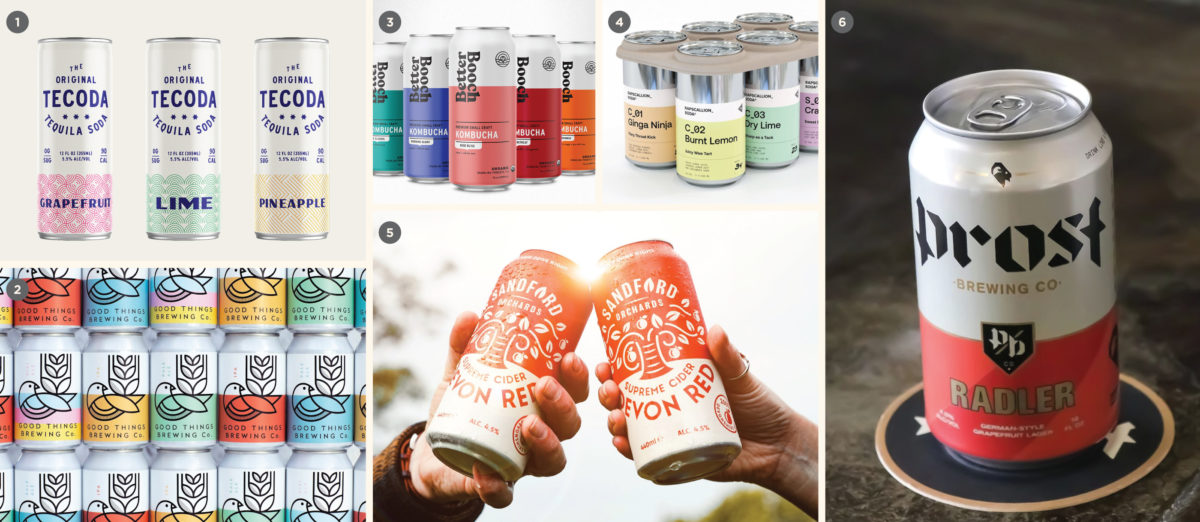

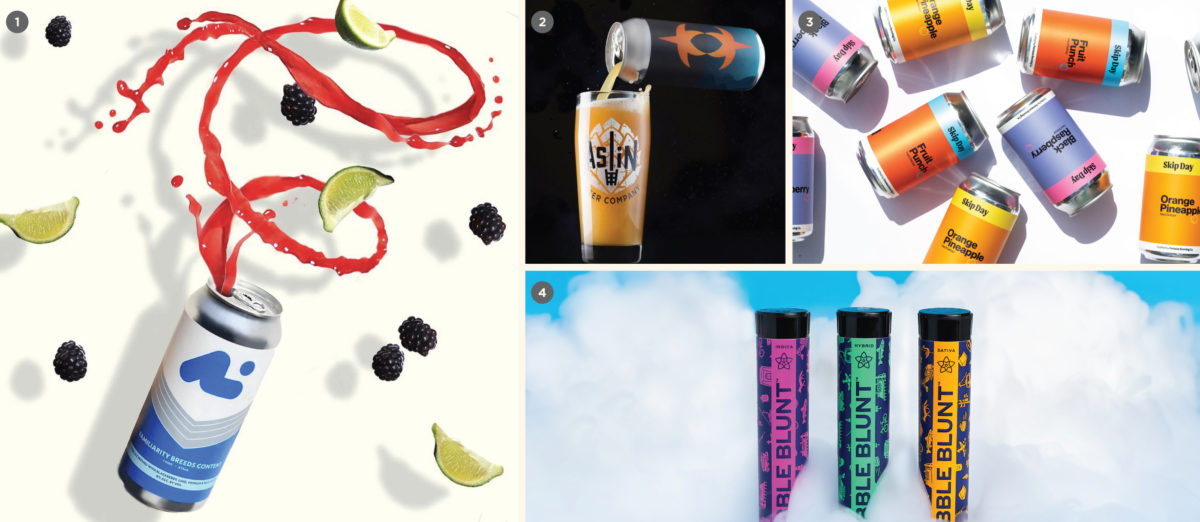

What do ready-to-drink (RTD) cocktails, hard seltzers, kombuchas, hard teas, functional beverages and craft beer all have in common? They’re almost universally packaged in cans. Throw in a few thousand breweries all scrambling to find additional cans as lockdowns went into effect in early 2020, and you have all the necessary ingredients for an aluminum shortage.

Here are some black and white numbers from Jamie Westfahl, vice president and head of procurement for Molson Coors. “We sell about 11.5 billion cans, on average, every year. So even a 5% swing is material. When demand goes up by 30% over a two-month period, we’re talking hundreds of millions of cans, and there’s just no way suppliers can meet that. It’s affecting the whole beverage industry.” With Ball and Crown building new plants and saying supply levels won’t return to normal until 2022 (at the earliest), the aluminum shortage is very real.

What other downstream effects does this bring?

Triaging the portfolio and/or retiring underperforming brands

We’ve watched breweries work through some tough decisions to shelve? No. Can? No, obviously not. Retire underperforming (and emergent) brands so they can focus on what sells well. If raw cans are at a premium, it might be hard to justify space in your portfolio for that fourth-place Scotch Ale, or even that seasonal Hefeweizen. There’s no telling whether these changes will be permanent, but my guess is that a lot of these contingency moves will become long lasting and perhaps permanent as the market adapts.

Other commodity shortages

This won’t make as many headlines as the can shortage, but corrugate, a.k.a. cardboard, a.k.a. the thing you use to create a branded box over your cans or a cool point-of-service (POS) stand or a tray, is facing increased demand as well. (How many cardboard Amazon boxes do you receive each week)?

Unless you were locked into a contract with a printer before the world went to hell last year, breweries who are boxing their beer could see some small increases in per-unit pricing until demand subsides.

Format changes?

Another downstream effect that could still happen is a brewery making an outright format change to get around the aluminum shortage. If cans aren’t available, just use bottles! Of course it isn’t that simple, and frankly, we haven’t seen anyone make this drastic a leap yet, though we’ve seen breweries who were previously only canning beer start to bottle some core brands as well.

We’ve also experienced a lot of in-process projects shift to whatever production format allows a brewery to hit their originally intended deadline. So a new line of seltzers that you were going to have Ball print might now have to be sleeved for the next 9 months while you wait for your spot in line to come up. (A heartfelt shout out to all you in-house designers and marketing folks that had to layout, re-layout and re-re-layout the same label across four or five different templates last year as you shifted between whichever vendors could get you those cans.)

We’ve even seen breweries use a variety of sleeved and pressure sensitive labeled cans for the same SKU in order to get beer out in into the market. We’ve also seen breweries gut wrenchingly label over an already printed can so they could get a higher performing beer out the door.

Nothing was off the table as the industry responded to COVID-19. And if you’re one of those beer industry folks that tap danced and pivoted and zigged and zagged your way through the last 15 months, keep it up. You’re doing great.

Convenience Stores

Let me get a 60 Minute IPA and 12 Roller Dogs. No time to explain.

There are a lot of misinformed opinions about convenience stores (C-stores): They only sell cheap beer. They only sell macro beer. No one would ever buy craft beer there (there would be no margin). I’m guilty of thinking this way myself before last year. But it turns out that, counterintuitive as it may be, C-stores can be a great channel for craft.

We spent a lot more time discussing craft beer in C-stores in 2020 than we have in the last 11 years. Larger craft breweries and distributors saw an opportunity in this channel as air travel ground to a halt. This is an interesting COVID-19 externality, and a viable opportunity for breweries who are able to get their beer into this setting.

To do this right, you need to be able to keep beer in this channel. The volume requirements are pretty steep with the average full turns happening in just over four days. You also need to get the format right. Single-serve sizes like 16oz cans, or more importantly, Stovepipes (19.2oz cans) work really well. Why? Because you can price them competitively and invite “trial”—it’s easier to take a chance on a $3 beer than spend $12 on a 6-pack you might not like.

Good Beer Hunting put together a great series (with a lot of metrics) on C-stores last year. Go check it out for more background.