Jeff Alworth

Author, Beervana Blog

It’s no secret that the beer industry is feeling anxious right now. I’d describe the posture as one of a defensive crouch. Unless you’re selling a mass market lager, the sky hasn’t fallen yet—but with the incursions of seltzer, dropping consumption rates, a slow bleed to other drinks, and the overwhelming proliferation of choice, it may feel like it to folks.

Given all that, I’m expecting retrenchment. I’ve seen a number of breweries’ release calendars, and they show less experimentation and more reliance on solid, perhaps even stolid, offerings. This isn’t too surprising—it’s what happened in the late 90’s and early aughts when the last slowdown happened. We went from a phase of wild experimentation, excess, and a general land-grabby atmosphere to a focus on doing things well, right, and just surviving.

These are all very speculative guesses, but in terms of beer, I would expect to see a return to what works and a period of refinement rather than experimentation. People are getting tired of gambling on mediocre beer, so they may reward consistency and quality. It’s not sexy, but brands that highlight these elements might weather the storm more easily. Everyone does the colorful, geometric can labels, but their punch may be wearing thin. I also wonder if bottles might enjoy renewed support (which means less breweries who use cans returning to bottles than bottling breweries defecting to cans).

In terms of beer, I expect hoppy ales to continue to be the main driver of interest, but I also expect brewers to back off the ledge at the extreme edge and move back toward a little bitterness and balance. Craft lager will continue to grow and I would expect most breweries will have to make one in the coming year or two.

I do expect there to be more churn and failures, and that will result in panic. We’re seeing the mass-marketification of craft fueled by excess capacity and anxiety, and that will certainly continue. Breweries will be spinning off side brands of FMBs, can cocktails, seltzers, etc. Regional breweries will have slicker, more corporate branding. I also expect Mexican lagers to recede somewhat.

There will surely be some unforeseen development that will rock the industry, but as such I cannot foresee its nature. Alcoholic milk? Calvados spritzers? Who knows. Beyond those things, about which I am surely more wrong than right, I’m just prepared to wait and see.

Bart Watson

Chief Economist, Brewers Association

So the first thing to say is that I think it’s harder to neatly summarize trends than in the past. With more breweries in more markets, you’re seeing lots of contradictory indicators, showing places where the market is going in multiple directions. This starts at the most basic level. The segment has never been stronger–more breweries, higher market share, more innovation, etc. but the market has never been so competitive. We’re still seeing demand grow, and along with it production, but it’s getting sliced more ways than ever before.

In general, growth is still strongest the smaller you are and the more local you are. While some regional craft breweries are still growing in broad distribution, that’s now a zero sum game more or less–collectively that space isn’t growing too much. Local is still a part of the demand and so there is space for smaller, nimble local players.

Moving into specific trends, I’ll highlight a couple. In packaging, as you already know, cans continue to gain share, in pretty much every format, though 12oz 6-packs are still the biggest chunk of the market. I have lots of data on this in a post that went up recently.

In styles, we see growth at both ends of the flavor/ABV spectrum and a hollowing of the middle. IPA is still the strongest growth style in craft, buoyed in recent years by the hazy/juicy variants, which appear to be bringing some new demographics into IPA. At the other end, there are signs of growth in a collection of lighter styles—lagers such as pilsner, but also things like blond ales, golden ales, and Kölsch. To me, this is the result of craft’s aging demographic (millennials shouldn’t be a synonym for young anymore) as well as the desire of more craft brewers to tap into the biggest part of the mainstream beer market that is more about crisp refreshment than it is about big bold flavors. Side diversion: that’s where seltzers play, but with some added things like low calorie, low carb, and gluten free that appeal to many drinkers. We’re going to see lots of brewers explore that space in 2020 and we’ll see if local has an opportunity there or if seltzer is more a brand (White Claw) than a true category. Session sours I think also play in this space in a way that may be more authentic for many craft brewers.

We’re going to see a lot of craft brewers try to put those trends together in 2020 in the form of low-cal IPAs. Will they work? No clue. It’s a hard balance to get flavor in a low ABV package, but hazy versions have a chance. Second side diversion: I wonder if calling a bunch of IPAs “low cal” is going to make some consumers question how many calories are in their existing IPAs, so I wouldn’t be surprised to see IPA growth take a hit in 2020 (though let’s be honest, it’s still going to grow).

This space isn’t just about ABV or calories, and I think more broadly reflects a desire on the part of beer drinkers to feel better about their choices and so I think there are growth opportunities here in ingredients and ingredient quality as well (local sourcing, etc.). That’s a smaller space, but it’s one that I think will grow, along with other niches like low/NA beer, organic, etc. They aren’t going to be huge, but they will all grow in 2020.

John Holl

Editor of Beer Edge: The Newsletter for Beer Professionals & host of the Drink Beer, Think Beer podcast

It’s Time to be Making Seltzer

If your brewery isn’t thinking about offering a hard seltzer, you’re missing out on the chance to bring new customers through the door, keep existing ones within your confines a little longer, and, oh yeah, making a few bucks along the way.

The amount of jokes heard batted around during the recent Great American Beer Festival about how it could soon be all about hard seltzer were a mixture of annoyance, astonishment, but not quite reassignment among the masses. There are still too many people who see the low-calorie, low-carb, clear fizzy sugar water as a flash in the pan, a fad that will come and soon go away.

It’s unlikely that hard seltzer will become a gateway beverage to beer. They are too dissimilar and reside in different parts of the occasion brain. But having one on offer for the customers who walk through your door and might ask for a hard seltzer means money in your pocket and someone who might stick around for longer than intended.

In this competitive marketplace if you’re not at least staying current you’re already behind.

Low Cal and Low Carb

As beer became a lifestyle over the last decade, it also became parts of other lifestyles. Even though big boozy IPAs and imperial stouts are still popular, there was a rise, especially over the last two years, in low-calorie, low-carb options for beer. Larger players like Michelob Ultra gained ground by talking to the fitness crowd and smaller breweries followed suit. Samuel Adams rebranded a Gose they had originally made for the Boston Marathon as 26.2, offering it as a post-race refreshment.

Other breweries like Deschutes began to offer 99 calorie lagers. And Avery got into the action with Pacer IPA, a hop forward and full-flavored Hazy IPA with 100 calories and 3.5 carbs. “Pacer IPA’s big flavor profile joins a growing lineup of lower calorie, lower carb options from Avery Brewing, like the recently released Rocky Mountain Rosé,” the brewery said when announcing the beer. “Pacer IPA brings a hazy and flavorful IPA to this functional category the brewery has named the Avery 100s. Adam Avery hopes to expand this exciting portfolio in the future.”

Walk into a brewery today and you’ll see yoga classes happening in the morning, cycling clubs showing up after a ride in the afternoon, sign-up sheets for hikes or athletic events and more. Whereas beer was once considered the beverage of choice for dudes with guts, they have been replaced by new generation of drinkers who want moderation and have a thought towards being health conscious.

This last decade also saw a shift to craft producers releasing non-alcoholic beers. In step with the low-calorie and low-carb options, non-alcoholic beer makers are refining the process that had existed for years (and often turned out beers few wanted to drink willingly) and creating IPAs, Stouts, and even Gose with little alcohol to be found.

Sales in the United States are still virtually non-existent against the rest of the category, but if we look to Europe where it’s currently 2 percent of the marketplace, there’s clearly demand and room to grow.

Expect More Breweries to Open and Close

Each year at the Craft Brewers Conference, an industry focused event, there are numbers produced about all the breweries-in-planning that have announced an intention to open. At the end of decade there were more than 1,000 that had announced desires to open. This might seem like a lot, but with 10,000 plus wineries operating in the country there’s obviously still room to grow, especially with so many small towns (and some major cities) lacking breweries to meet a population’s needs.

It’s true that most of the breweries that open from this point on won’t become large brewing companies in the scales of say, Sierra Nevada Brewing Co. or New Belgium Brewing, but by producing a few hundred or even a few thousand barrels per year the owners can carve out a nice niche and be an important part of a local community.

The question many have been asking, especially those who pay close attention to the beer industry, is if there is a bubble or glut of breweries and will it soon burst. While it’s impossible to know, it’s important to note that businesses closing is not uncommon. It happens with restaurants all the time.

In some cases, like with Boulder Beer, which has been open since 1979, breweries are choosing to shrink rather than grow their footprints to keep the bottom line strong.

Because beer fans are so passionate, when closings happen it feels more acute. It’s just common sense to realize that with so many breweries there are going to be some that close. Some will be because of financial hardships, while others will simply decide to move on from the industry. Businesses will change hands from one generation to another and the successors might find that they didn’t have the same passions as their parents or grandparents.

Still others might decide that when it’s time to retire–and remember there’s a whole generation of craft beer pioneers that are hitting that stage–they want their legacy to remain with them and they’ll simply close their doors rather than pass a brewery on through a sale.

The end of the last decade saw a lot of closures. Beer writer Jeff Alworth dubbed October 2019 as “black October” after a good number of breweries shuttered their doors for good, many unexpectedly. For the next few years we can expect much of the same around the country.

Taylor Williams

Brand Manager, Craft Roads Beverage (craft distributor)

Evolving Distribution Strategy: Short and Sweet

From a wholesaler standpoint, 2019 saw the emergence of an abbreviated distribution model that will shake up the market moving into 2020. This short and sweet strategy allows breweries to enter a new market for a short duration with a limited number of offerings, giving retailers a constantly rotating tap list of fresh beer and satisfying the insatiable consumer demand for new beer. This means the “rotation nation” mentality of the craft beer industry won’t be losing any steam in 2020.

The Guest Brewer program from Kwapil’s Brew Pipeline and Craftroads Pioneer Series are successful examples of the limited distribution model.

In this same vein, as the already saturated market crowds further, we expect to see an uptick in mergers and acquisitions as established brands scramble to maintain their foothold in the industry. Brands like Avery, Founders and Platform, who were bought out in the previous year, can now weather the storm of over-saturation under the comfort of a large financial umbrella. Big beer buy-outs and international investments become increasingly tempting as more brands and alternative beverage options clamor for the limelight.

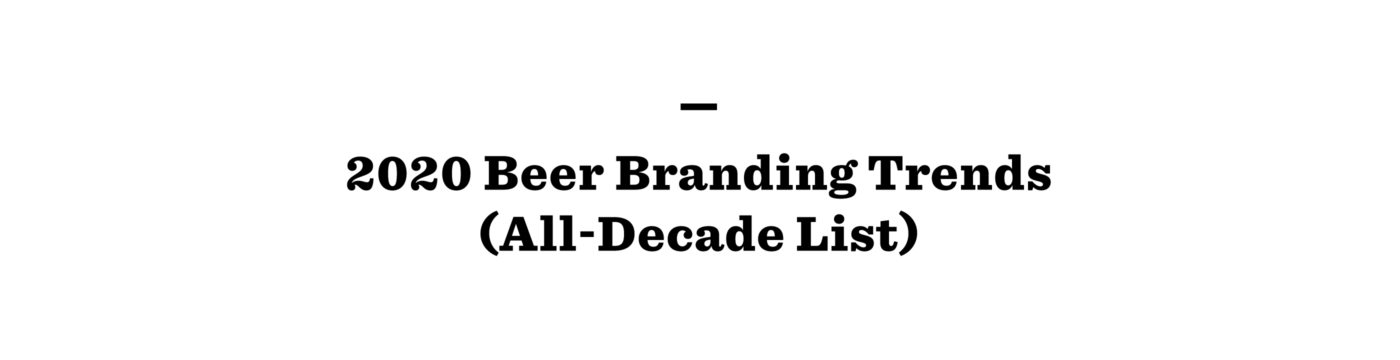

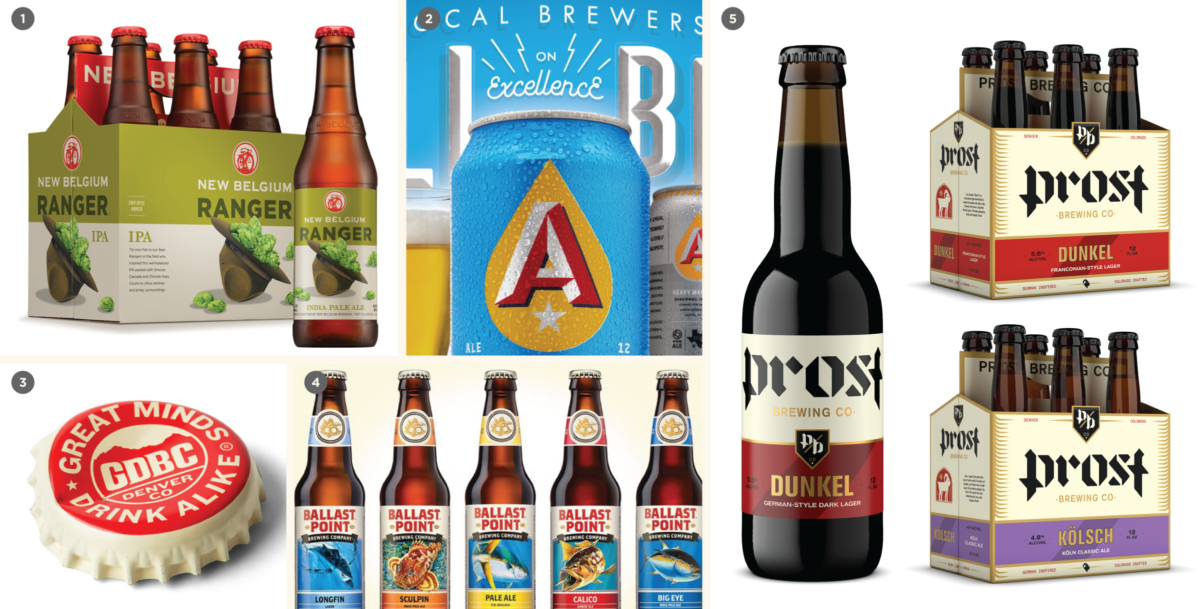

Old Dogs, New Designs

In 2020, we’ll see more brands dedicate time and resources to not only owning a great tasting beer but owning a great looking beer. If we learned anything in 2019, making great beer isn’t enough.

Sun King Brewing refreshed several of their can designs and expanded packaging options within the past year, Avery Brewing premiered a brand overhaul complete with new can designs in 2018, and Oskar Blues just debuted their first major redesign in more than a decade. 2020 will put to the test the selling power of a well-executed brand makeover.

The Sparkling Elephant in the Room

Seltzer. Spiked seltzer. Spiked seltzer EVERYWHERE. Combine low calorie and low carb with a reasonable 5% ABV, and you have the 2020 triple threat of alcoholic beverage.

While Truly and White Claw will dominate the category across the country, we’ve seen national and regional craft breweries key in to the potential consumer growth of adding a little boozy bubbly to their line-up. Brands like Platform and Avery, as well as the big beer brands, wasted no time creating and distributing what is likely to be the biggest beverage trend of 2020.

New Year, New Beer: Healthy-ish Beverage Growth

Our number one requested brand in 2019 was not a hazy IPA or milkshake stout, it was our gluten-free option. Along with the low-cal seltzer option, the demand for gluten-free and alcohol-free beer, and even spiked kombucha, will increase as the craft consumer population grows more health conscious.

Juan Matias Zubillaga

CEO, Cerveza Ocaso (Buenos Aires, Argentina)

It’s an exciting time in Argentine beer. Regarding beer trends, many NEIPAS to be found, many using locally-grown hops like Victoria, Mapuche, Cascade and Nugget. Also a trend on fruited beers, like our Tropical APA with pineapple.

It is a very ale-focused market, not so many lagers in sight. We have 2 lagers of 5 beers in our year round portfolio which is more than the average. There are some wild things going on with Brut yeast, some IPLs and also some beers being made with wine grapes. Aging beer in wooden barrels from our wine region—Mendoza being the most common because of their availability. Not so much in liquor barrels.

Of the 2,000+ microbreweries around, there are no more than 5 with a canning line (including us). This number will grow over the next several years.

Mandie Murphy

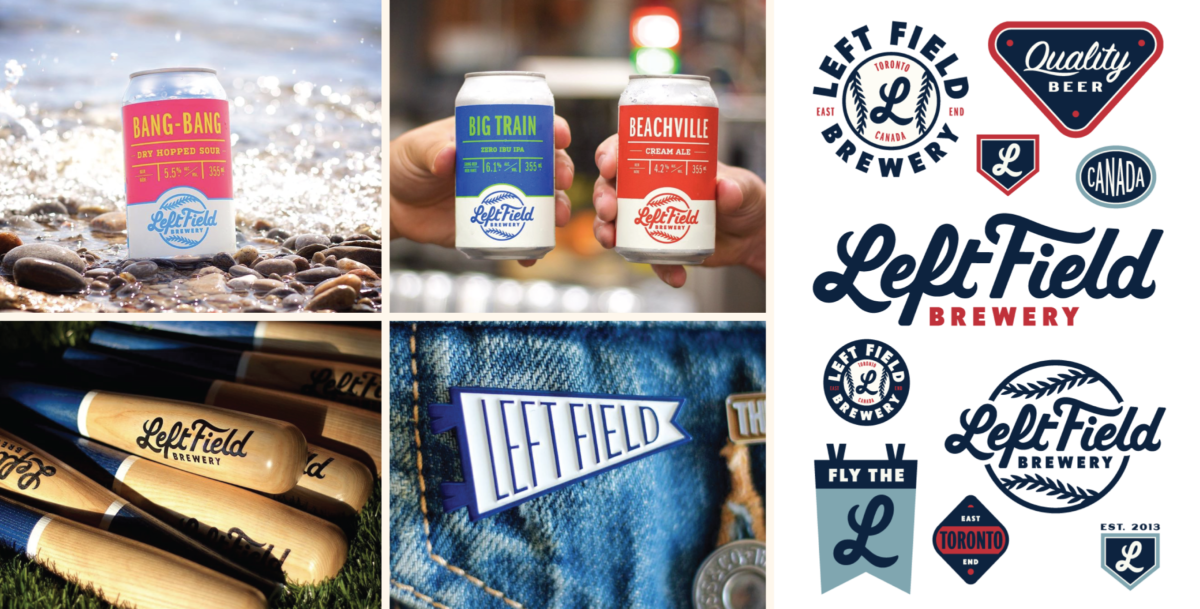

Co-Founder, Left Field Brewery (Toronto, Ontario)

The Hazy IPA and Fruited Sour trend doesn’t seem to be slowing down as far as we can tell. We see them both in their own way, attracting new drinkers to craft from other categories like wine and cider. This is especially true with sours, where you can now find at least one sour on tap in most corporately owned chain restaurants.

We are seeing a resurgence of well made clean, crisp lagers including a number of new Pilsner releases, some with a terroir focus such as the Italian Pilsner. More recently, some examples of lager hybrids are showing-up, making drinkers think about lagers in new ways.

Low ABV offerings are very on trend and some wine-beer hybrids have started popping-up more commonly in our market as well.